Drawing of Leonardo from collection of Francesco Melzi. Royal Library, Windsor. The Royal Collection.

Leonardo Da Vinci died 500 years ago on 2 May 1519. Born illegitimate and separated from his mother as a child he became the archetypal Renaissance Man and reputedly died in the arms of the Francis I, king of France. Although chiefly remembered as an artist in modern culture, his curious and creative mind engaged across many fields of enquiry. Outside of is painting, his inventions are still celebrated, often with exaggerated claims. Nevertheless, his official job, when he had one was City Engineer where he was engaged in construction of city defences and waterworks. In 2007 I had the opportunity to explore Leonardo’s scientific mind, when his Codex Leicester was loaned to the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin by Bill and Melinda Gates.

The Codex Leicester, Leonardo’s draft for a treatise on water contains such a diversity of sciences including astronomy, atmospherics, geology, hydraulics and mechanics. It provides a fascinating insight into one of the most interesting minds of history as he explores the physical world. Leonardo The Codex Leicester: Reflections on the water and the moon attracted 80,000 visitors in the Summer of 2007. Calmast developed a programme of interpretation of the science in the codex and constructed 6 interactive exhibits based on Leonardo’s writings and drawings. For the 500th anniversary of his death, I reproduce some of the material from 2007 below.

Codex Leicester at the Chester Beatty Library

This is a great year for science awareness in Ireland, the Blackrock Castle visitor centre opens, the Exploration Station plans are unveiled and Leonardo da Vinci visits Dublin. Well, Leonardo’s scientific notebook, the Codex Leicester is visiting at any rate and will be on display at the Chester Beatty Library until August 12th. Written 500 years ago, the Codex Leicester comprises 72 pages of text written in his characteristic mirror writing and startling illustrations relating his observations, investigations and theories of the physical world. The 72 pages are written in ink on the left and right and front and back of 18 sheets of linen. The front (A) and back (B) of the 18 sheets are displayed in the specially remodelled gallery at the Chester Beatty. The codex is owned by Bill and Melinda Gates and is loaned out to museums worldwide. It is a tremendous achievement for the Chester Beatty to bring the Codex to Ireland as it is sought after by some of the largest and most famous museums in the world. The Chester Beatty Library, European Museum of the Year 2002, has one of the most important collections of near Eastern and Far Eastern material and is able to display the Codex in the company of relevant and contemporaneous works, many of which influenced Renaissance thinkers and some of which were read by Leonardo. Many of the displayed works prompt us of the importance of Islamic scholars who preserved classical knowledge, added to it and reseeded European learning and others remind us of the rich history of Chinese science and technology. Accompanying these are interactive displays developed by CALMAST, which recreate Leonardo’s investigations from the Codex Leicester. These interactives bring the Codex to life giving visitors the opportunity to understand and appreciate Leonardo’s scientific explorations.

Da Vinci didn’t know everything and he didn’t invent everything, in fact many of his designs were impractical and many of his beliefs incorrect but Leonardo doesn’t need exaggeration or hagiography: he achieved so much is so many areas. Known generally as an artist he left us only a few paintings, but some of the most important ever painted and certainly one, the Mona Lisa the most famous. After his paintings his inventions are probably best known, the helicopter and flying machine, the tank and automobile, did he even build the first robot? In fact he was employed as an engineer and spent a great deal of his time on science. There is little awareness of his scientific work and even his tremendous investigations in anatomy are often explained as a painter dissecting to better represent the body. Leonardo’s interest in anatomy wasn’t inspired by his art rather his art and science were inspired by a burning curiosity and facilitated by an amazing faculty of observation. Leonardo also did extensive investigations in the areas of optics and geometry, which were also related to his painting through perspective and light. He conducted studies in acoustics, astronomy, geology, natural history (especially the flight of birds), mechanics and the nature and flow of water. The nature and flow of water is the main theme of the Codex Leicester.

The Renaissance Man

Leonardo was born in 1452 near the village of Vinci west of Florence. The most famous man of the Renaissance would have been expected to have a more auspicious start in life. Leonardo’s mother Caterina was a peasant girl, his father Ser Piero was a notary and his father was a land owner. So marriage was out of the question – at least with Caterina – Ser Piero went on to marry three times, each match good for his career but this start in life barred university and the professions for his first born son. Brought up on the farm by his grandparents and uncle Francesco, Leonardo would have spent his childhood close to nature whetting his curiosity and honing his powers of observation. In his early teens Leonardo became an apprentice in a leading studio in Florence that of Andrea del Verrocchio. Florence was at the centre of the greatest movement of European thought in over a millennium. The Renaissance was to allow Leonardo the painter and subsequently the engineer and scientist to flower.

The Renaissance was a time of new ideas, but largely it was about the rediscovery of classical learning. Greek learning had been transmitted through Islamic scholars and the fall of Constantinople when Leonardo was a baby saw Greek scholars flee to Italy for refuge. In engineering, architecture and art Europeans had not been able to match the works of Greece and Rome, but 15th Century Italians began to match and even surpass the ancients in art, architecture and engineering. The understanding of the natural world was heavily influenced by scripture and classical thought. Even Leonardo followed the Aristotilean view of the four elements: earth, water, wind and fire and in the Codex Leicester he explains many phenomena in these terms. Refreshingly, he shows contempt for alchemists and astrologists and although Leonardo never fully emerges from this classical world view he does sound very modern at times.

Codex Leicester

So what of the Codex Leicester? It is full of questions but Leonardo has three major scientific questions relating to: luminosity of the moon, the occurrence of fossils on mountains and the circulation of water. He begins with the earth, sun and moon. Using beautiful drawings, he advances his theory about light reflecting from the moon, which he reasons must be covered in water to allow such reflection. Remarking that many believed the moon to be a convex mirror he argues that if it were we would only see the light reflected from a small portion of it making the moon appear smaller and much brighter. The reflections from the waters on the moon indicate that the water must be in waves and that of course, proves that there is also wind there. While we know this to be incorrect, Leonardo did not have the benefit of the telescope. In this portion of the Codex (sheet 2A) he becomes the first person to correctly explain the lumen cinereum: that the shaded portion of the crescent moon is faintly visible to us because of the reflection of the sun’s light from the earth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Codex Leicester Sheet 2A detail showing the lumen cinereum .

Leonardo holding the classical belief that microcosm reflects macrocosm, considers the earth like the body of an animal with veins circulating a life-giving fluid, water.

“The body of the earth like the bodies of animals is interwoven with a network of veins which are all joined together, and are formed for the nutrition and vivifying of this earth and of its creatures; and they originate in the depths of the sea, and there after many revolutions they have to return through the rivers formed by the high burstings of these veins.”

Leic. 4A 33v (translation: McCurdy )

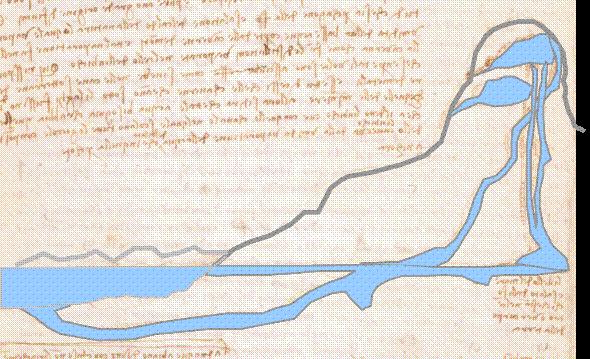

Figure 2. Codex Leicester Sheet 3B detail. Coloured to show Leonardo’s water cycle

In the drawing on sheet 3B (Figure 2, coloured for clarity as the original is faint) Leonardo illustrates his theory. He thinks that these veins originate in the bottom of the sea and run under the land and up through mountains where they burst through as springs and form rivers. These rivers then bring the water back to the sea.

Leonardo uses this theory to explain how rivers can start near the tops of mountains. He doesn’t believe that rain could be the cause and he also argues that rivers flow in dry areas where there is no rain. But, he has to explain how the water flows up through these veins. He proposes and tests a number of ideas: capillary action (as in a sponge), evaporation and condensation and syphonage. He explores these mechanisms in other pages of the codex. However Leonardo couldn’t come up with a convincing explanation for this movement of water because his theory was wrong! Leonardo did much better in his observations of rivers after they rise. He correctly explains how rivers wear away soil and rocks and describes how they carve out valleys:

“….the persistent action of the rivers … cut through the mountains; and the rivers in their wandering courses carried away the high plains enclosed by the mountains; and the cuttings of the mountains are shown by the strata in the rocks which correspond to the sections made by the said courses of the rivers.”

Leic 1B 1v (translation: Richter )

Figure 3. Codex Leicester

Sheet 1B detail showing mountains on the earth and rock strata.

On a subsequent page he predicts that eventually the mountains will be levelled by water erosion:

“How in the end the mountains will be levelled by the waters, seeing that they wash away the earth which covers them and uncover their rocks, which begin to crumble and subdued alike by heat and frost are being continually changed into soil. The waters wear away their bases and the mountains fall bit by bit in ruin into the rivers.”

Leic 17B (translation: Richter )

His studies of droplets of water and bubbles, illustrate his powers of observation and careful recording.

Figure 4. Codex Leicester

Sheet 12B detail showing a bubble on a reed.

“Water attracts other water to itself when it touches it: this is proved from the bubble formed by a reed with water and soap, because the hole through which the air enters there into the body and enlarges it, immediately closes when the bubble is separated form the reed, running one of the sides of its lip against it opposite side, and joins itself with it and make it firm.”

Leic 12B (translation McCurdy)

On sheet 10B he gives this beautiful observation of a falling drop of water:

“That water may have tenacity and cohesion together is quite clearly shown in small quantities of water, where the drop, in the process of separating from the rest, before it falls becomes as elongated as possible, until the weight of the drop renders the tenacity by which it is suspended so thin that this tenacity , overcome by the excessive weight, suddenly yields and breaks and becomes separated from the aforesaid drop, and returns contrary to the natural course of its gravity, nor does it move from there any more until it is again driven down by the weight which has been reformed.”

Leic. 10B (translation McCurdy)

He goes on to draw two conclusions from this observation firstly

“that the drop has cohesion and nerve structure in common with the water with which it is joined; secondly that the water drawn by the force breaks its cohesion, and the part that extends to the break is drawn up by the remainder in the same manner as is the iron by the magnet.”

A major question for Leonardo is how sea shells are found in rocks up mountains a great distance from the sea. Most people believed that they were carried up from the sea by the Biblical Deluge. Many people even suggested that they grew in the rocks. Leonardo dismisses the “stupidity and ignorance of those” saying “such an opinion cannot exist in brains possessed of any extensive powers of reasoning”.

“In this work of yours you have first to prove how the shells at a height of a thousand braccia were not carried there by the Deluge, because they are seen at one and the same level, and mountains also are seen which considerably exceed this level, and to enquire whether the Deluge was caused by rain or by the sea rising in a swirling flood; and then you have to show that neither by rain which makes the rivers rise in flood nor by the swelling up of the sea could the shells being heavy things be driven by the sea up the mountains or be thrown there by the rivers contrary to the course of their waters.”

Leic. 1B (translation McCurdy)

Leonardo reasoned that sea shells could not have been carried up by flood waters as they sink in water. To those who suggest that sea shells could have crawled up there, he points out that forty days is not long enough for shells to travel hundreds of miles. He also points out that if sea creatures were carried up by the flood they would be all broken and mixed up together, like on a beach. However, they are found gathered in the same manner as they would be found on the sea shore.

“If the Deluge had carried the shells for distances of three and four hundred miles from the sea it would have carried them mixed with various other natural objects all heaped up together; but even at such distances from the sea we see the oysters all together and also the shellfish and the cuttlefish and all the other shells which congregate together, found all together dead; and the solitary shells are found apart from one another as we see them every day on the sea-shores.”

Leic. 9B (translation Richter)

Leonardo believed that the rocks were formed under the sea by deposition and correctly reasons therefore that the sea once covered the mountains. This was far ahead of his time However, he believed that the sea level fell uncovering the mountains rather than the land rose up from the sea. It was not for almost another 300 years that James Hutton, the “father of modern geology” proposed that land folded up into mountains. Hutton also famously claimed that the “present is the key to the past”.

Three centuries earlier in the Codex Leicester Leonardo says that the rocks are a testament to time, writing

“Since things are more ancient than letters, it is not to be wondered at if there is no record of how the aforesaid seas extended over so many countries ….Sufficient for us is the testimony of things produced in the salt waters and now found again in the high mountains, sometimes at a distance for the seas.”

Leic 6B (translation McCurdy)

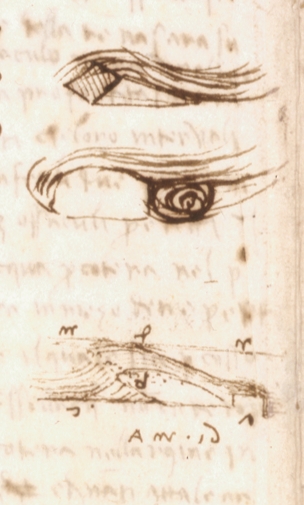

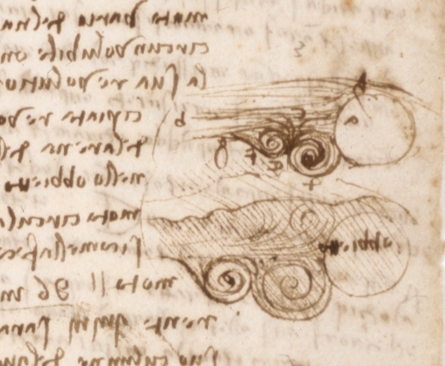

The behaviour of flowing water is of significant interest to Leonardo the Engineer, designer of bridges, canals and flow control in rivers. In the Codex he presents a series of compelling drawings of water flow around obstacles, showing eddy formation for different shapes (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)). These drawings compare well to 20th Century photographic investigation into fluid flow. He examines waves in great detail reporting experiments with wave propagation and reflection in bowls of water. He investigates several mechanisms for moving water, such as syphonage and the relationship between flow from a vessel and depth of liquid in the vessel.

Figure 5 (a) and (b). Codex Leicester Sheet 13A details showing water flow over and around obstacles

Leonardo even finds time to investigate the reason why the sky is blue hundreds of years before Rayleigh and Tyndall:

“I say that the blue which is seen in the atmosphere is not its own colour but is caused by warm humidity evaporated in minute and imperceptible atoms on which the solar rays fall rendering them luminous against the immense darkness.”

Leic 4A (translation Richter)

Leonardo’s Scientific Legacy

How do we assess Leonardo the scientist? It is easy to assess his influence on modern science – it was very little. Why? Because during his life he didn’t publish his theories; he didn’t even manage to organise is findings in a very coherent manner- they were spread over more than 10,000 pages of notes. The Codex Leicester importantly, is one of the most organised and gathered works. After his death efforts to organise his work were soon abandoned, it didn’t help also that the notes were in Italian and mirror writing and jumped from one subject to the next; the notebooks were split up and dispersed, the drawings being valued. Alas, by the late 19th century serious efforts were made to mine his works, most of his scientific work had been discovered by others or disproved. While Leonardo doesn’t need exaggerated praise, he doesn’t deserve detractors but inevitably he had to be assailed by those to whom revisionism is bread and butter. Some even challenge Leonardo’s right to the mantle “scientist”. Leonardo was not a modern scientist in the fullest sense, but saying he is not a scientist is like saying his contemporary Columbus was not an explorer because he didn’t use GPS and he ended up in the wrong place. A brief encounter with the Codex Leicester will quickly convince the reader of Leonardo’s place in the history of science.

About the author

Eoin Gill, an

Engineering lecturer at Waterford Institute of Technology, co-manages CALMAST,

the Centre for the Advancement of Learning of Maths Science and Technology with

Sheila Donegan at WIT. Eoin and Sheila are current EU Descartes Laureates for Science Communication through the written

word and they recently received the first ever national Science, Engineering and Technology

Awareness Award from Engineers Ireland.

References

Translations are taken from the following books.

The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Edward MacCurdy, 1939.

The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, Jean Paul Richter, first published 1883.

Images are details from © Seth Joel / Corbis Corporation

Further reading:

A catalogue has been published by the Chester Beatty Library for the exhibition.

“Leonardo da Vinci The Codex Leicester” edited by Michael Ryan, with essays by Philip Cottrell, Michael John Gorman and Dorothy Cross and is available at the Chester Beatty Library.